Code, publicly-available data, and figures for this post are available on this Github repository.

Significant effort in the social sciences is spent on properly measuring economic well-being. Statistics covering income receive much of this attention, partly because the data underlying these statistics are easily accessible. However, income is an incomplete measure: it typically measures the flow of resources for an individual or family over a month or a year but not the stock of resources. Statistics based on this stock of resources, more commonly known as wealth, offer an arguably better view of inequality in the U.S.

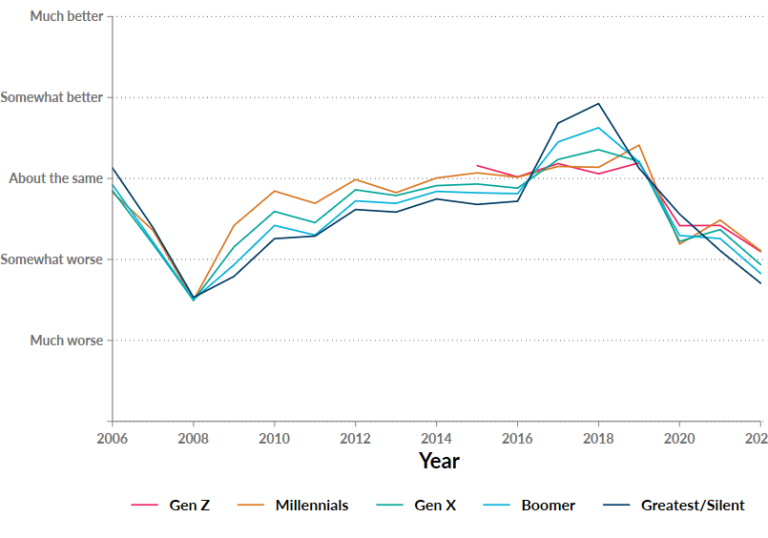

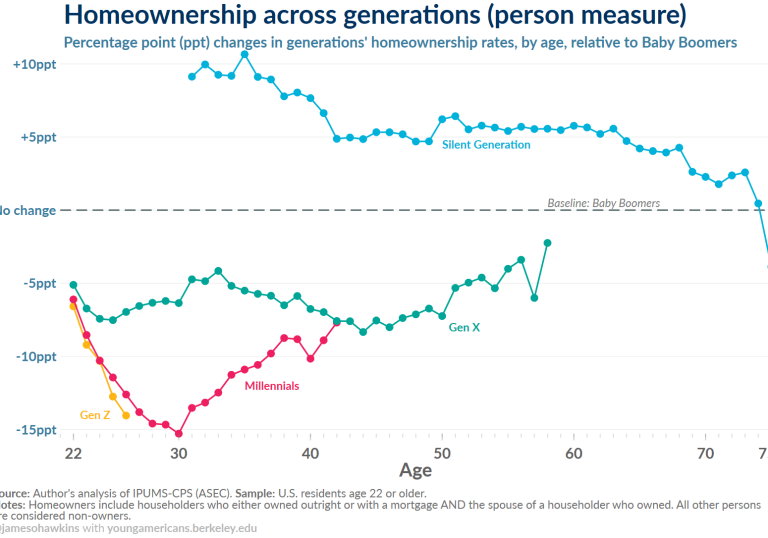

One of the primary sources of data covering the wealth of U.S. families comes from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) – a triennial survey conducted by the Federal Reserve. SCF-based wealth, or net worth, includes all of the components of family resources, including but not limited to the total value of cash savings, stocks, bonds, vehicles, and real estate. The SCF is also a critical source for measuring wealth at different ages – many analyses of wealth in the SCF focus exclusively on measuring how wealth is increasing (or declining) among various age groups or generations over time. These SCF-based statistics of young adults receive significant attention from the popular press, think tanks, scholars, and the Federal Reserve itself, which regularly updates a measure of wealth across generations and age using data based in part on the SCF. All of this attention is understandable since these statistics help address a fundamental economic question: are younger generations of Americans financially better/worse off than previous generations?

Despite the focus on estimates of wealth across age groups, this issue brief presents evidence showing that too little attention is paid to whether these wealth statistics are representative of young adults (and other age groups).