The Berkeley Institute for Young Americans is a research partner of the California 100 initiative, a statewide initiative focused on inspiring a vision and strategy for California’s next century that is innovative, sustainable, and equitable. In a recently published report, we took a look at how California governs and funds its early care and education (ECE), K-12, and higher education systems, and identified strengths and shortcomings across the different sectors.

In this post, we review the key takeaways from our evaluation of the state’s higher education system to make the case that California needs an adequacy formula to better fund each of the state’s higher education segments.

As we describe in more detail in this post, California has ambitious aims for higher education. Lawmakers established goals in the state’s education code to expand college access to more students, improve college affordability, and ensure that more students are prepared for the 21st century labor market. Achieving such goals across the state’s massive higher education system is no easy task and requires that colleges and universities have the resources necessary to meet the challenge.

Like many other states, lawmakers in California do not use an adequacy definition or formula to fund higher education in order to achieve statewide goals. Instead, most spending decisions come down to ‘back of the envelope’ calculations and political decision-making. In our evaluation of California’s higher education finance system, we found that the lack of an adequacy formula has led to consequences for students and higher education institutions, namely, increases to student tuition, overcrowded campuses, and ongoing cost pressures in campus budgets that are overlooked in state funding decision-making.

While developing adequacy formulas in higher education are still in their nascent stage, the topic should be of interest to those who want to design a more adequate and equitable funding model for the country’s largest higher education system. Defining an adequacy formula could help more people access a high quality degree program and complete their degree without mounting student debt, and could provide higher education institutions with the resources necessary to prepare students for the demands of the 21st century workplace.

What is an adequacy formula?

In its simplest definition, adequacy addresses how much funding a student needs to achieve a certain outcome or goal, such as graduation from college. It is important to note that modern legal definitions of adequacy often recognize that the amount needed for all students to achieve certain goals or outcomes may vary across students, colleges, and universities.

This means that equitable funding is often associated with adequacy to ensure that the finance system compensates for the cost of educating students from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Therefore, any adequacy definition must account for additional programs, services, and other resources that disadvantaged students require so that each student has the support they need to achieve desired goals.

The conceptualization of adequacy (and equity) formulas are rooted in K-12 finance, but researchers have begun to take many of the concepts and apply them to higher education.

(Note: Lawmakers have experimented with another type of funding formula for higher education institutions in recent years–performance-based funding. In fact, California’s community colleges currently use a performance-based funding model. For more information, see our higher education finance issue brief.)

How much does California currently spend on higher education?

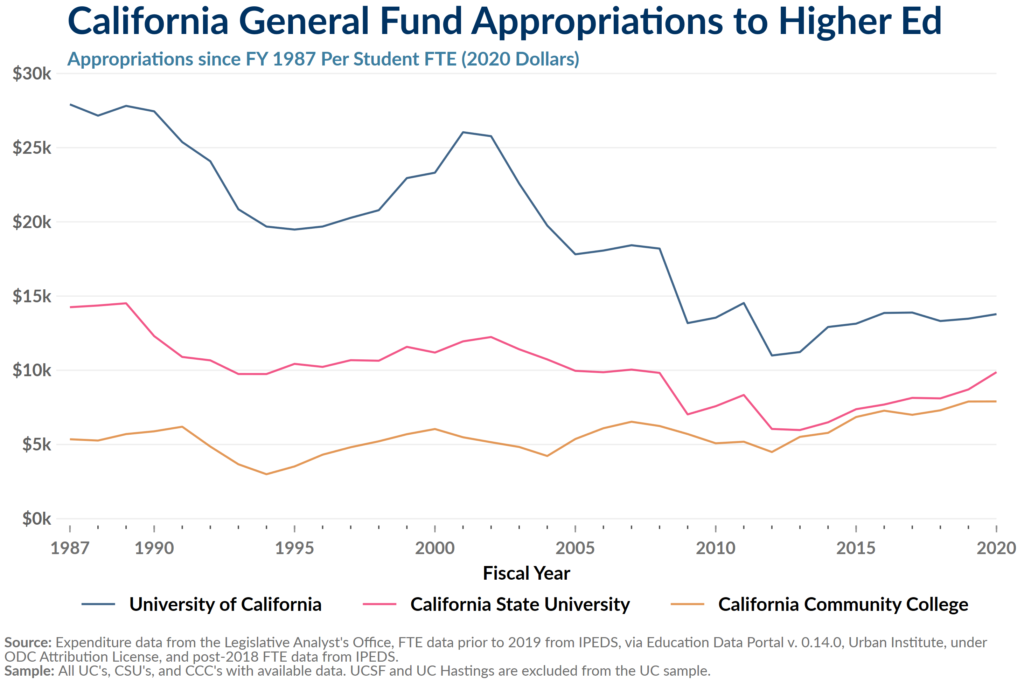

In Figure 1 below, we show state appropriations for higher education over time. State appropriations to the University of California (UC) system in 2020 are half of what they were in 1987. In the same time period, California State University (CSU) appropriations dropped by 31 percent while California Community Colleges (CCCs) did notably better with a 48 percent increase in state appropriations over the time period shown.

State funding for CCCs has likely grown over time since the majority of funding for the segment is tied to Proposition 98, which allocates a percentage of the state’s General Fund to K-14 education. In a typical year, K-14 education will receive about 40 percent of the state’s General Fund revenue; community colleges should statutorily receive 10.93 percent each year, but in most years they receive less than that share. No such budgetary protections exist for the UC and CSU systems, which is a primary reason why funding has declined for those segments.

Since California does not use an adequacy formula or definition to fund higher education, there is no guarantee that students or colleges and universities will receive adequate funding in any given year, leading to adverse consequences for higher education institutions and students, especially during economic recessions. According to a report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, during the 2008 Great Recession, California drastically reduced higher education spending over several years; in response, the state’s public 4-year colleges on average experienced a 63 percent tuition increase between 2008-2017.

Figure 1

Goals of the higher education system

To determine whether current funding levels are adequate to meet the needs of the higher education system, we next take a look at the goals put forth by lawmakers and whether students are reaching the state’s goals. Language added to the education code by SB 195 states that higher education policy and budget decisions should adhere to the following goals:

1) to improve student success and access, especially for low-income students;

2) to better align degrees and credentials with the state’s economic, workforce, and civic needs; and

3) to ensure the effective and efficient use of resources to improve outcomes and maintain affordability. Below, we review each of these goals in turn.

Goal #1 – Expand college access and improve completion rates

In recent years, lawmakers have narrowed in on issues of college access, rates of degree completion, college affordability, and labor market outcomes across the state’s higher education segments. In part, this focus was triggered by a 2005 report from the Public Policy Institute of California that identified a ‘skills gap’ highlighting the difference between the level of education the future California population was likely to possess versus the level of education demanded in the state’s future economy. Indeed, a mismatch persists even today between the demand for those with college degrees and the current supply.

College access

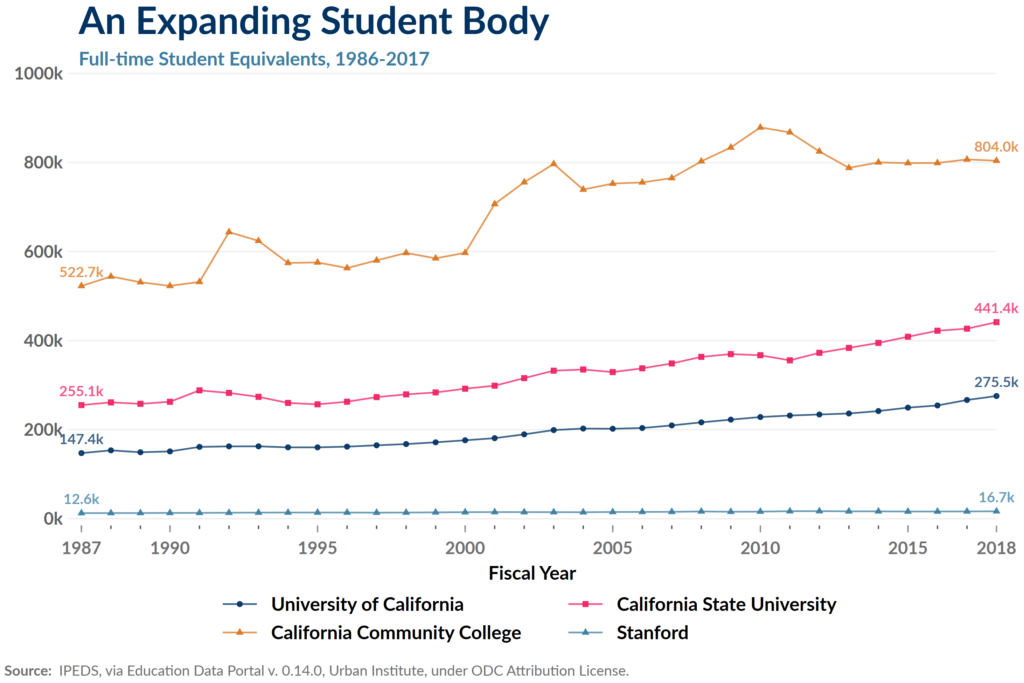

As seen in Figure 2, in an attempt to expand college access, California’s higher education segments have been enrolling many more students over time. However, in recent years, the CSU reached its enrollment limits, and began rejecting thousands of qualified freshman applicants each year, many of whom were disadvantaged students. This has led the CSU to engage in a process referred to as “impaction,” which raises admission requirements when they cannot accommodate the number of applicants; CSUs are also redirecting applicants to campuses where there is enrollment space, rather than to the applicants’ first choice college. CSUs in particular have pushed many students into online programs since it has exceeded its capacity to accommodate in-person instruction, and now serves one third of students in partial or fully online programs. In a turn of events, the pandemic has caused some CSU campuses to have a surplus of enrollment spots since attendance at community colleges—that typically feed students to the CSU system—have experienced enrollment drops.

UCs have been responding to new enrollment increases by increasing class sizes, increasing student to faculty ratios, and neglecting investment in facility maintenance and growth, decisions that will likely have an effect on education quality (Douglass & Bleemer, 2018). Recently, the UC Board of Regents voted to increase tuition in the coming years to address increasing enrollment and reduce the risk of diminishing educational quality further.

Given the limited space within California’s public higher education system, it may come as no surprise that more and more high school graduates are leaving the state altogether to attend college. The Public Policy Institute of California (2019) found that this number doubled from 2004 to 2017, with over 36,100 students exiting the state, of which half enrolled at out-of-state public universities. The latest data from the CCC Chancellor’s Office also shows that while CCCs have been successful in transferring more students to the UC and CSU systems over the past five years, many more students are also transferring to out-of-state or private in-state colleges and universities. Of special concern is the fact that the majority of Black students attending a 4-year college enroll in private, for-profit institutions that charge higher tuition and often leave students with much higher student debt levels.

In the latest 2022-23 budget, lawmakers significantly increased funding for the state’s higher education system, in part to address the issue of growing student enrollment. However, whether the ongoing commitments made in the budget will be sustained in the years ahead is an open question given the state of the economy and current revenue forecasts. An adequacy formula—if written into law —could help state lawmakers make more precise estimates to allocate resources to programs and services that are necessary to give access to higher education pathways for more students, and guarantee that ongoing funding would be available from year-to-year.

Figure 2

College attainment

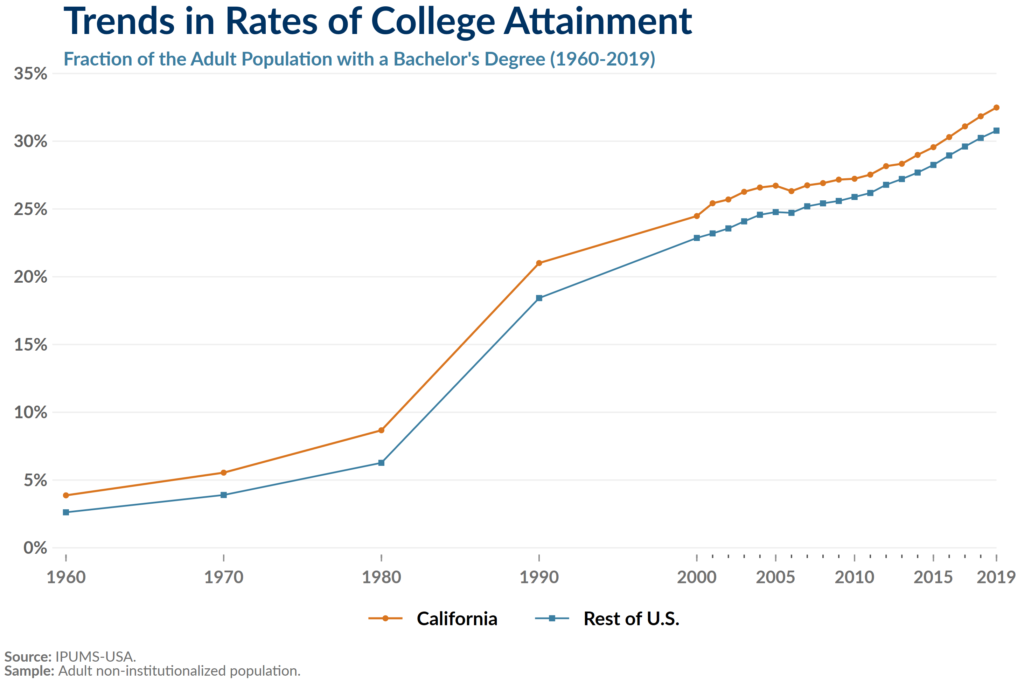

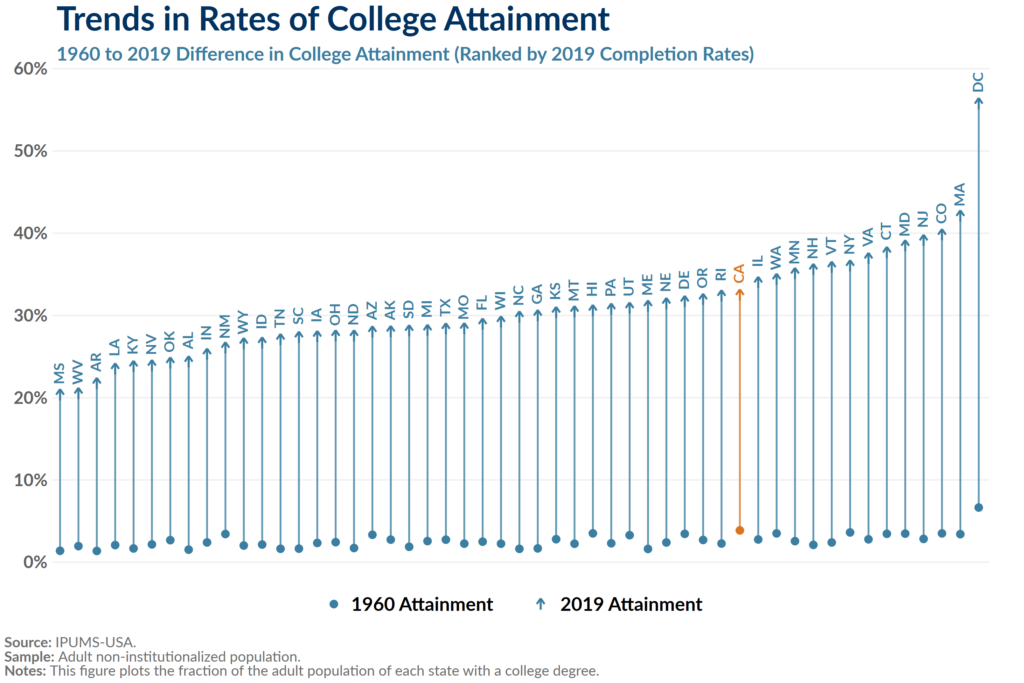

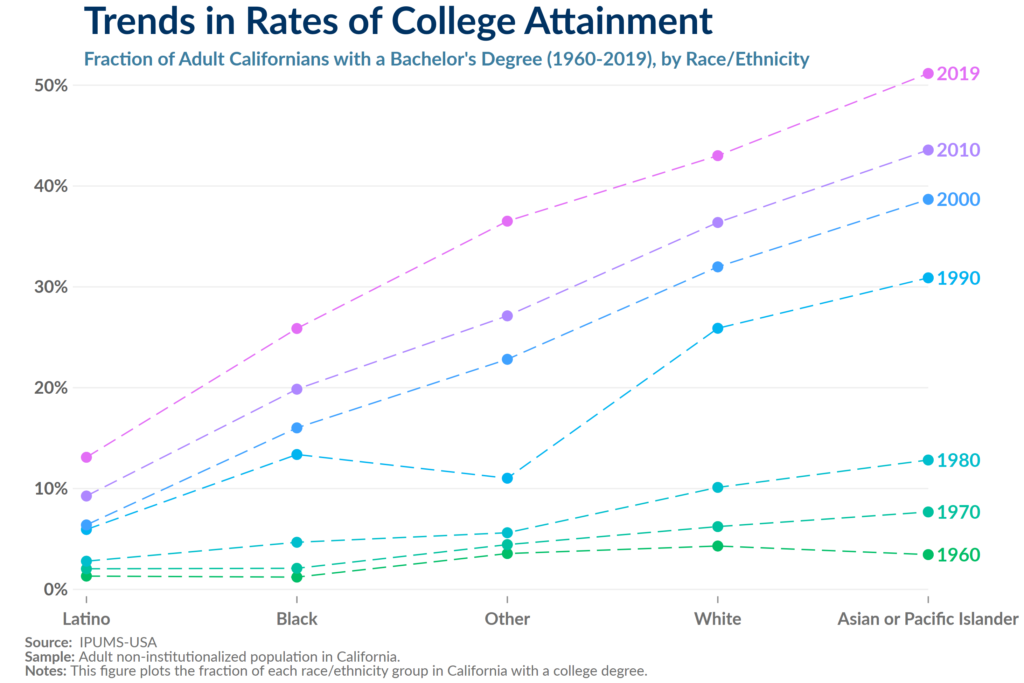

There is promising news for California’s college attainment rates: overall, more Californians than ever before now have at least a Bachelor’s degree. In Figures 3 and 4 below, we show that, over the past sixty years, college attainment rates in California have risen dramatically—ranging from just 3.9 percent of the adult population with a college degree in 1960 to about a third of the population in 2019. College attainment rates in California and the rest of the U.S. have closely tracked each other; however, California has consistently outranked the rest of the U.S. by several percentage points. In fact, when ranked against other states, California falls in roughly the top third of states that have improved college attainment rates the most over the last several decades. Some of the fastest growth in the share of the adult population with college degrees occurred from 1980 to 1990 when the percentage of the population with a college degree in California more than doubled. The past ten years also saw relatively strong growth in college completion, with the rate of population-wide Bachelor’s degrees growing from 27.2 percent in 2010 to about 32.5 percent in 2019.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Yet there are concerns when breaking down these trends by race/ethnicity. In Figure 5, we plot the same college attainment measure by race/ethnicity and find that California has a long way to go in boosting college attainment rates equally for all. Since 1960, college attainment rates by race/ethnicity in California have become more unequal, with the college attainment rates of Asian/Pacific Islander and white adults rising far faster than the rates for Latino, Black, or “other” races. As of 2019, college completion rates for Latino adults lagged significantly behind other groups, with only 13 percent of Latino adults in 2019 having completed a 4-year degree.

Figure 5

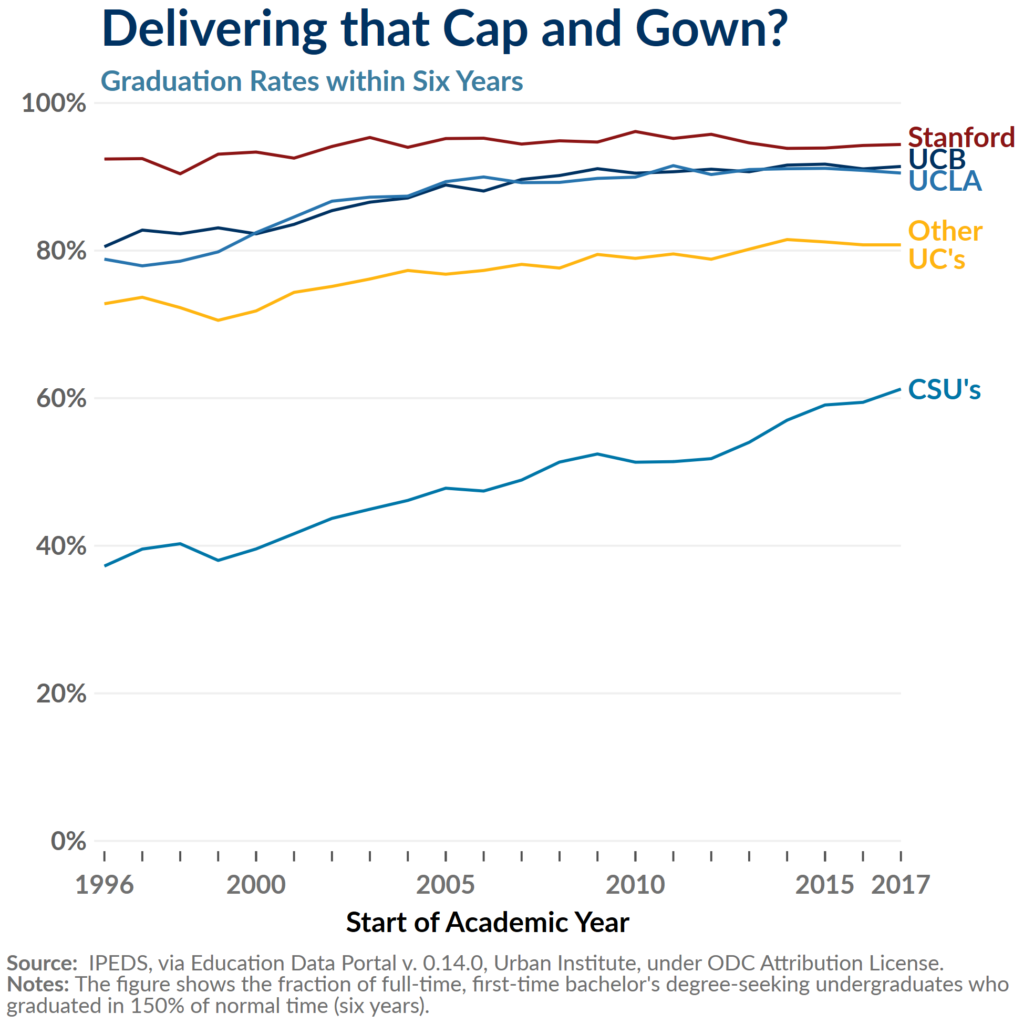

In Figure 6 below, we show how graduation rates by institution have changed over time. The CSU system has increased graduation rates from about 40 to 60 percent in the time period shown, but still falls far below their UC counterpart in graduating students. UCs have seen growth that is more modest, hovering at about 80 percent. Stanford has the highest graduation rate at upward of 90 percent. Trend lines are also shown for UC Berkeley and UCLA, which have both improved graduation rates over the time period shown but still trail Stanford.

An adequacy formula would help provide the resources necessary for the three segments to serve the unique needs of students who enroll, while also providing the financial support required to improve overall retention and graduation rates.

Figure 6

Goal #2 – Ensure more students graduate from college ready for the 21st century labor market

In today’s rapidly changing economy, there is a new demand placed on adult learning to ensure that individuals can be successful in the evolving economy and labor market, which is being transformed by technology in the form of artificial intelligence and automation. Some argue that to be successful in this new economy, students must learn how to become self-guided, life-long learners, which means that workers will need to continually return to postsecondary education to upskill, retrain, and reskill.

In a review of existing literature, we found that California’s higher education institutions lack the organizational infrastructure for adult and life course education that is necessary for the 21st century economy. Several lawmakers and researchers have pointed out that the state’s Master Plan, in particular, fails to meet the demands of students and has become outdated for the transformations taking place across the economy. Moreover, some argue that the design and structure of the state’s higher education system impedes coordination between the three segments to meet regional workforce needs across the state (Berman et al., 2018; California Competes, 2017; Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, 2018).

Major organizational impediments such as transfers between the CCCs and UCs and CSUs, enrollment capacity limitations, and limited opportunities for continuing education and adult learning are restraining the state’s ability to produce 21st century workers that are necessary for today’s economy. Each of these limitations come with cost pressures that could be addressed with an adequacy formula.

Goal #3 – College affordability

In light of rising student tuition in California and nationally, financial aid programs have been the primary policy lever to increase access to higher education and improve retention and graduation rates. Financial aid programs are widely available from both the federal government and from California state-funded programs, as well as from local institutional aid.

In California, the state has several financial aid programs to offset the cost of tuition for low-income students, including Cal Grants, student fee waivers like the California College Promise Grant, and a range of other programs that target low- and moderate-income students. A 2019 study found that state aid in California outpaces federal Pell grant aid; the state spends more than $4,000 per low-income student on financial aid, making California one of the country’s most generous states for student aid programs. In fact, about half of all students across the three higher education segments–especially low-income students–pay no tuition at all. This plays out in the total student loan debt students take on in California versus nationally–The Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS) finds that the average California undergraduate takes out $21,125 in student loans compared to the national average of $29,096. In recent years, the California economy and state budget have been growing and state lawmakers have chosen to expand existing aid programs or in some cases created new aid programs to support students in their higher education journey.

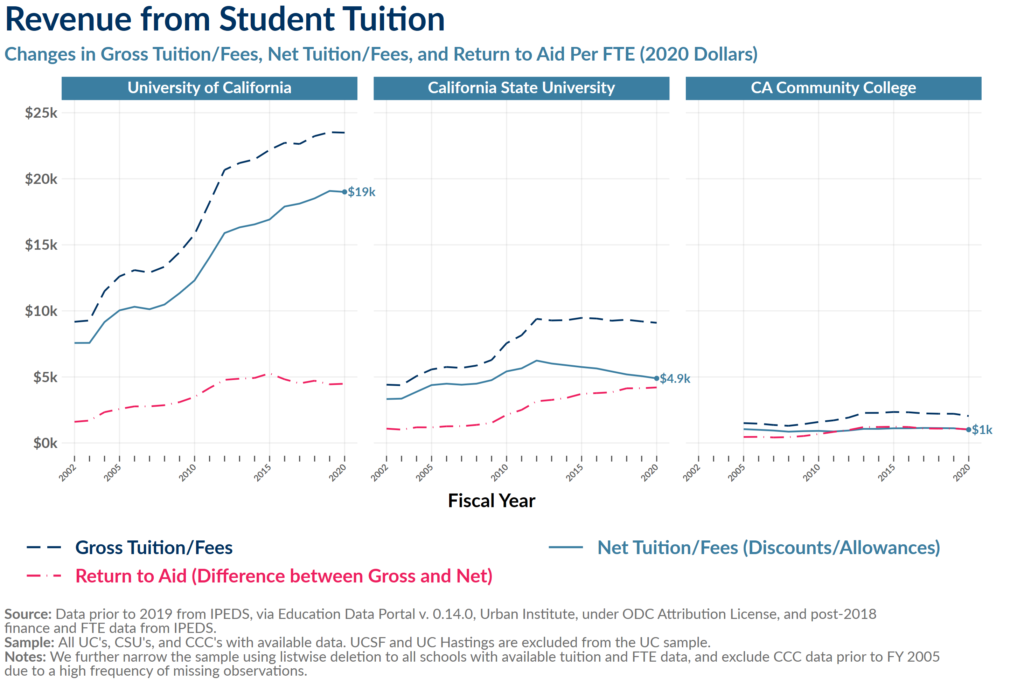

At the institution level, many colleges and universities across the state provide their own grants and scholarships. It has also become common practice for universities to reinvest a portion of their tuition revenue into need-based aid (also called return-to-aid), where the goal is to reduce costs for lower- and middle-income students while charging higher-income students the “sticker price”. As seen in Figure 7 below, we show how one primary revenue source—tuition—has fluctuated across three categories: gross tuition, net tuition (the amount of money that can actually fund system budgets), and return to aid (gross minus net). In 2020, among all of the public higher education systems, UC had the highest net tuition/fees at $19k, followed by CSU at $4.9k, and CCC at $1k. Notably, institutional return to aid kept overall tuition and fees from being even higher (reaching the gross tuition/fees line)–at the UC and CSU systems, return to aid was about $4.5k and $4.2k, respectively, and $1k at CCCs.

Figure 7

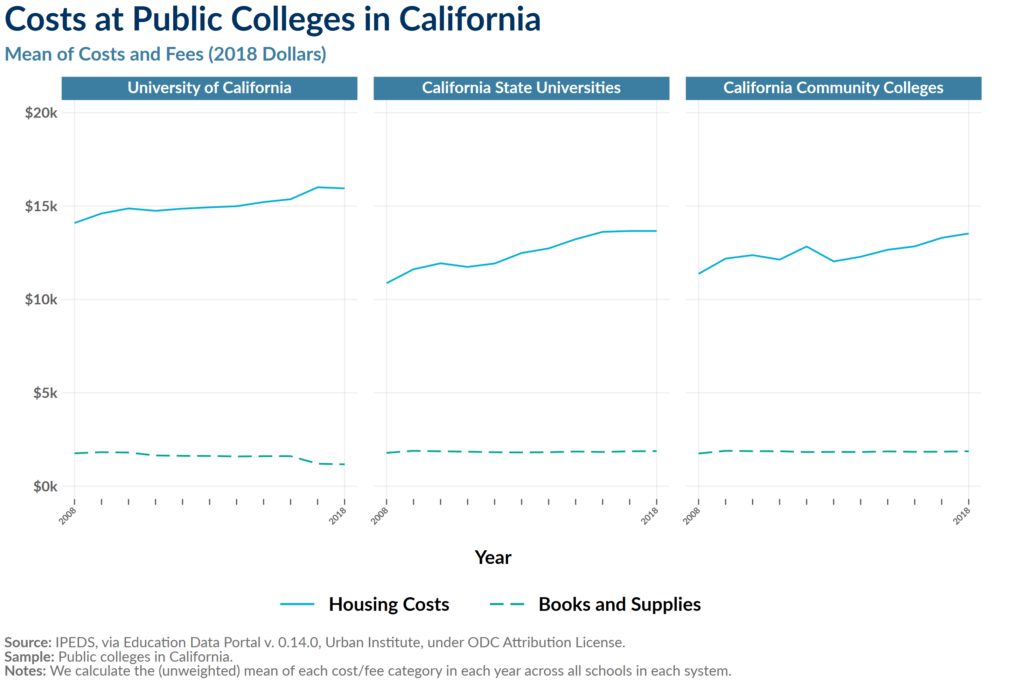

However, financial aid programs do not account for the total cost of college attendance, including the costs of living. The cost of books and supplies, housing, transportation, and childcare are especially high in California, making it difficult for many students to afford even basic needs. In fact, researchers from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) estimate that when taking into account these other basic needs, the total cost of attending one of the UCs is closer to $32,000, with tuition and fees accounting for just 42 percent of the overall price tag. At CSUs, they estimate the total cost to be just under $15,000, with tuition and fees representing just a third of the total cost; and while community colleges have very low tuition, tuition is just 12 percent of total costs, which PPIC researchers estimate to be over $10,000.

In Figure 8 below, we show our own estimates of housing costs and the cost of books and supplies for students across each of the three higher education segments over time. As seen, the cost of books and supplies has remained fairly steady across all three segments, but the cost of housing has increased, with the highest housing costs estimated for the UC system. Given the cost pressure of the housing market, it may come as no surprise that all the UC graduate student workers went on strike in fall 2022 to negotiate higher wages. The state could greatly benefit from an adequacy approach to financial aid that considers the cost of living in financial aid packages.

Figure 8

Consequences of not having an adequacy formula

California’s lack of an adequacy formula has real consequences for higher education institutions and students, most notably, an increase in net tuition and growing cost pressures that are overlooked in state appropriation decision-making.

Increases in net tuition

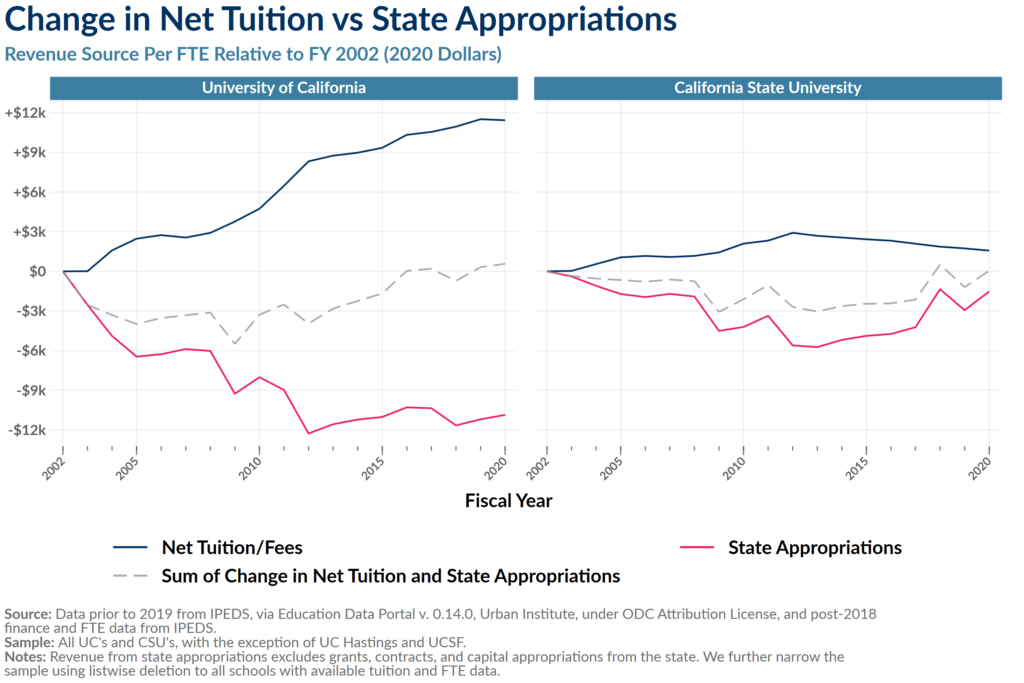

A consequence of state appropriation declines is that students have seen stark increases in net tuition since the early 2000s (gross tuition minus any allowances/deductions to students). In Figure 9, we show how net tuition and state appropriations have changed over nearly two decades. State cuts have been sharpest in the UC system over the last two decades and have generally outpaced any increases in net tuition on an FTE-adjusted basis. Since 2011, however, some of the Great Recession era cuts to the UC system were modestly reversed while net tuition continued to increase. Relative to 2002, the state had cut appropriations by about $10,900 per FTE by 2020 while tuition rose to $11,400 per FTE in the same year. The CSU system has fared better in terms of state cuts, and therefore students in those systems have experienced less severe tuition increases. Much of the post-2001 cuts to the CSU’s were reversed in the 2012 post-recession period. The increase in net tuition at CSU’s reached a peak of close to $3,000 in 2012 but has since been on the decline.

Figure 9

Cost pressures

The three higher education segments are facing serious cost pressures, most notably from deferred maintenance costs for campus infrastructure and rising pension costs. While the state historically funded a significant portion of the UC’s capital outlay, in 2013-14, the state legislature decided to no longer fund the UC’s capital budget through state bonds or other state resources. Instead, the UC is now expected to issue their own bonds to fund capital projects and pay for the debt service on these bonds out of general operating funds. The state took a similar action with the CSUs in 2014-15. Both university systems also face a backlog of capital projects due to aging infrastructure and the increasing cost of seismic compliance.

Rising pension costs have also had a large impact on higher education budgets. During the Dot Com bubble in the late 1990s state pension funds were performing well and the state legislature passed legislation that greatly increased pension guarantees for state workers and allowed workers to retire at earlier ages. Yet assumptions about stock market gains and the stability of the economy were shortsighted— returns on pension investments dropped precipitously when the Dot Com bubble burst, and unfunded pension liabilities have continued to grow since that time. During the recession that followed, the state stopped providing subsidies for pensions and health benefits for UC employees altogether. In response, the UCs were forced to pick up full pension funding, significantly affecting the University’s overall financial stability. On the other hand, the state has continued to fund these pension costs for the CSUs and community colleges.

The bottom line

State lawmakers have clearly defined the goals of the higher education system: to expand college access and improve graduation rates, align degrees and credentials with the demands of the 21st economy, and ensure the effective use of resources to maintain affordability. However, the state legislature has demanded more of the higher education system without adequately funding the segments to reach these new goals. A lack of an adequacy formula has led to consequences for students and higher education institutions, namely, increases to student tuition, overcrowded campuses, and ongoing cost pressures in campus budgets that are overlooked in state funding decision-making. California would greatly benefit from an adequacy formula that is fully funded from year-to-year so that all students can achieve the goals established by lawmakers. For a deeper dive on this topic, see our issue brief series on higher education finance and governance.